News

Stay informed about the latest developments in Gaza, the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Lebanon.

493 items found

Killed Saving Lives

25 November 2025

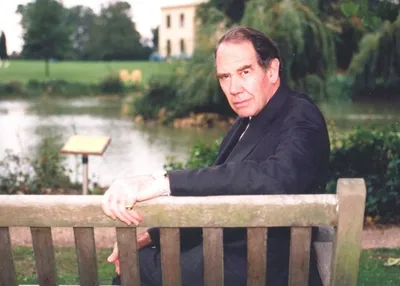

MAP appoints Steve Cutts as CEO

17 September 2025